Estimating Generalized Linear Models for Continuous Data with rstanarm

Jonah Gabry and Ben Goodrich

2025-12-30

Source:vignettes/continuous.Rmd

continuous.RmdIntroduction

This vignette explains how to estimate linear and generalized linear

models (GLMs) for continuous response variables using the

stan_glm function in the rstanarm package.

For GLMs for discrete outcomes see the vignettes for binary/binomial and count outcomes.

The four steps of a Bayesian analysis are

- Specify a joint distribution for the outcome(s) and all the unknowns, which typically takes the form of a marginal prior distribution for the unknowns multiplied by a likelihood for the outcome(s) conditional on the unknowns. This joint distribution is proportional to a posterior distribution of the unknowns conditional on the observed data

- Draw from posterior distribution using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC).

- Evaluate how well the model fits the data and possibly revise the model.

- Draw from the posterior predictive distribution of the outcome(s) given interesting values of the predictors in order to visualize how a manipulation of a predictor affects (a function of) the outcome(s).

This vignette primarily focuses on Steps 1 and 2 when the likelihood is the product of conditionally independent continuous distributions. Steps 3 and 4 are covered in more depth by the vignette entitled “How to Use the rstanarm Package”, although this vignette does also give a few examples of model checking and generating predictions.

Likelihood

In the simplest case a GLM for a continuous outcome is simply a linear model and the likelihood for one observation is a conditionally normal PDF \[\frac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{2 \pi}} e^{-\frac{1}{2} \left(\frac{y - \mu}{\sigma}\right)^2},\] where \(\mu = \alpha + \mathbf{x}^\top \boldsymbol{\beta}\) is a linear predictor and \(\sigma\) is the standard deviation of the error in predicting the outcome, \(y\).

More generally, a linear predictor \(\eta = \alpha + \mathbf{x}^\top \boldsymbol{\beta}\) can be related to the conditional mean of the outcome via a link function \(g\) that serves as a map between the range of values on which the outcome is defined and the space on which the linear predictor is defined. For the linear model described above no transformation is needed and so the link function is taken to be the identity function. However, there are cases in which a link function is used for Gaussian models; the log link, for example, can be used to log transform the (conditional) expected value of the outcome when it is constrained to be positive.

Like the glm function, the stan_glm

function uses R’s family objects. The family objects for continuous

outcomes compatible with stan_glm are the

gaussian, Gamma, and

inverse.gaussian distributions. All of the link functions

provided by these family objects are also compatible with

stan_glm. For example, for a Gamma GLM, where we assume

that observations are conditionally independent Gamma random variables,

common link functions are the log and inverse links.

Regardless of the distribution and link function, the likelihood for the entire sample is the product of the likelihood contributions of the individual observations.

Priors

A full Bayesian analysis requires specifying prior distributions

\(f(\alpha)\) and \(f(\boldsymbol{\beta})\) for the intercept

and vector of regression coefficients. When using stan_glm,

these distributions can be set using the prior_intercept

and prior arguments. The stan_glm function

supports a variety of prior distributions, which are explained in the

rstanarm documentation

(help(priors, package = 'rstanarm')).

As an example, suppose we have \(K\)

predictors and believe — prior to seeing the data — that \(\alpha, \beta_1, \dots, \beta_K\) are as

likely to be positive as they are to be negative, but are highly

unlikely to be far from zero. These beliefs can be represented by normal

distributions with mean zero and a small scale (standard deviation). To

give \(\alpha\) and each of the \(\beta\)s this prior (with a scale of 1,

say), in the call to stan_glm we would include the

arguments prior_intercept = normal(0,1) and

prior = normal(0,1).

If, on the other hand, we have less a priori confidence that the parameters will be close to zero then we could use a larger scale for the normal distribution and/or a distribution with heavier tails than the normal like the Student t distribution. Step 1 in the “How to Use the rstanarm Package” vignette discusses one such example.

Posterior

With independent prior distributions, the joint posterior distribution for \(\alpha\) and \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) is proportional to the product of the priors and the \(N\) likelihood contributions:

\[f\left(\boldsymbol{\beta} | \mathbf{y},\mathbf{X}\right) \propto f\left(\alpha\right) \times \prod_{k=1}^K f\left(\beta_k\right) \times \prod_{i=1}^N {f(y_i|\eta_i)},\]

where \(\mathbf{X}\) is the matrix

of predictors and \(\eta\) the linear

predictor. This is the posterior distribution that stan_glm

will draw from when using MCMC.

Linear Regression Example

The stan_lm function, which has its own vignette, fits regularized linear models using a

novel means of specifying priors for the regression coefficients. Here

we focus using the stan_glm function, which can be used to

estimate linear models with independent priors on the regression

coefficients.

To illustrate the usage of stan_glm and some of the

post-processing functions in the rstanarm package we’ll

use a simple example from Chapter 3 of Gelman and Hill

(2007):

We shall fit a series of regressions predicting cognitive test scores of three- and four-year-old children given characteristics of their mothers, using data from a survey of adult American women and their children (a subsample from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth).

Using two predictors – a binary indicator for whether the mother has

a high-school degree (mom_hs) and the mother’s score on an

IQ test (mom_iq) – we will fit four contending models. The

first two models will each use just one of the predictors, the third

will use both, and the fourth will also include a term for the

interaction of the two predictors.

For these models we’ll use the default weakly informative priors for

stan_glm, which are currently set to

normal(0,10) for the intercept and normal(0,5)

for the other regression coefficients. For an overview of the many other

available prior distributions see

help("prior", package = "rstanarm").

library(rstanarm)

data(kidiq)

post1 <- stan_glm(kid_score ~ mom_hs, data = kidiq,

family = gaussian(link = "identity"),

seed = 12345)

post2 <- update(post1, formula = . ~ mom_iq)

post3 <- update(post1, formula = . ~ mom_hs + mom_iq)

(post4 <- update(post1, formula = . ~ mom_hs * mom_iq))stan_glm

family: gaussian [identity]

formula: kid_score ~ mom_hs + mom_iq + mom_hs:mom_iq

observations: 434

predictors: 4

------

Median MAD_SD

(Intercept) -10.1 13.7

mom_hs 49.5 15.3

mom_iq 1.0 0.1

mom_hs:mom_iq -0.5 0.2

Auxiliary parameter(s):

Median MAD_SD

sigma 18.0 0.6

------

* For help interpreting the printed output see ?print.stanreg

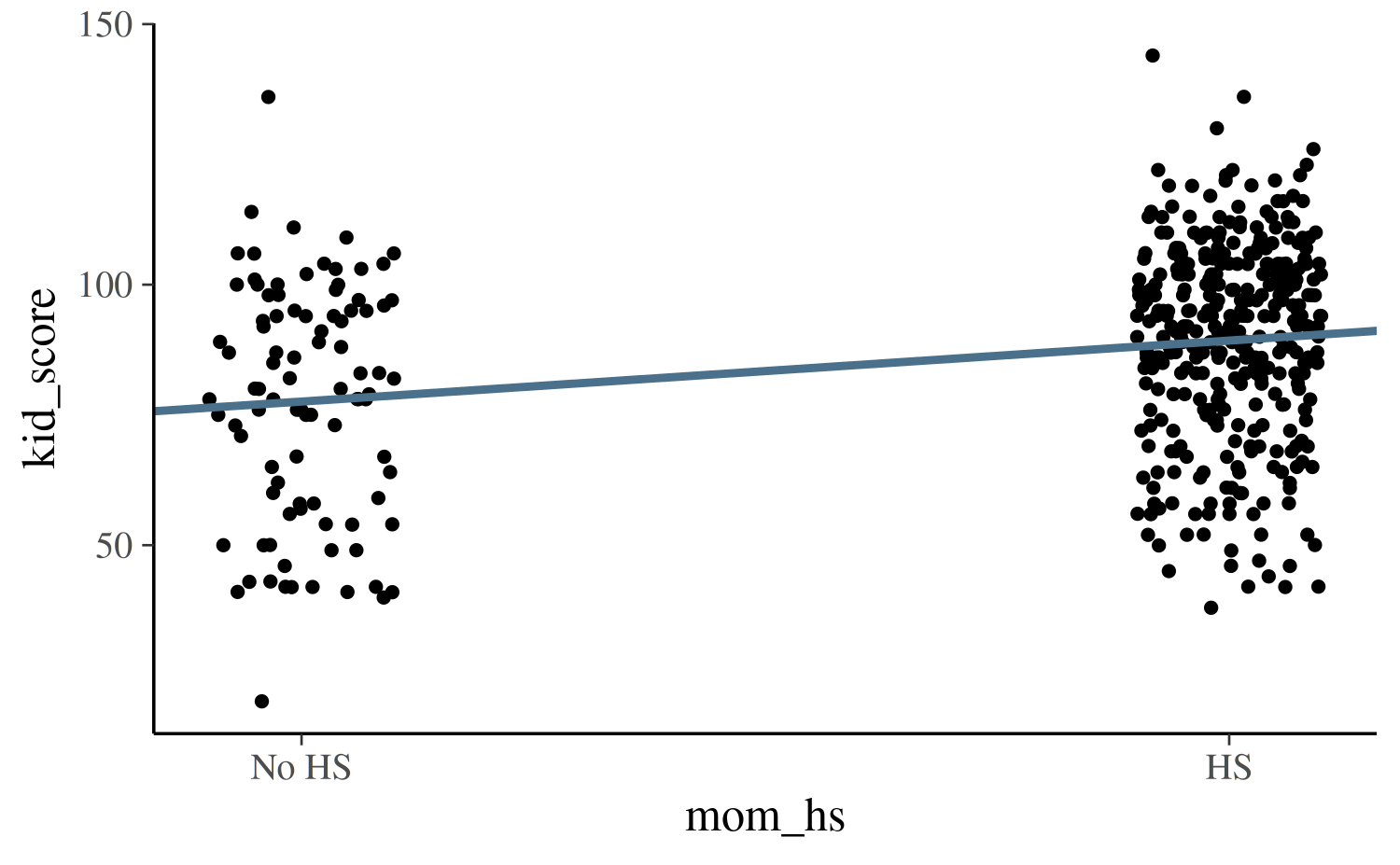

* For info on the priors used see ?prior_summary.stanregFollowing Gelman and Hill’s example, we make some plots overlaying the estimated regression lines on the data.

base <- ggplot(kidiq, aes(x = mom_hs, y = kid_score)) +

geom_point(size = 1, position = position_jitter(height = 0.05, width = 0.1)) +

scale_x_continuous(breaks = c(0,1), labels = c("No HS", "HS"))

base + geom_abline(intercept = coef(post1)[1], slope = coef(post1)[2],

color = "skyblue4", size = 1)

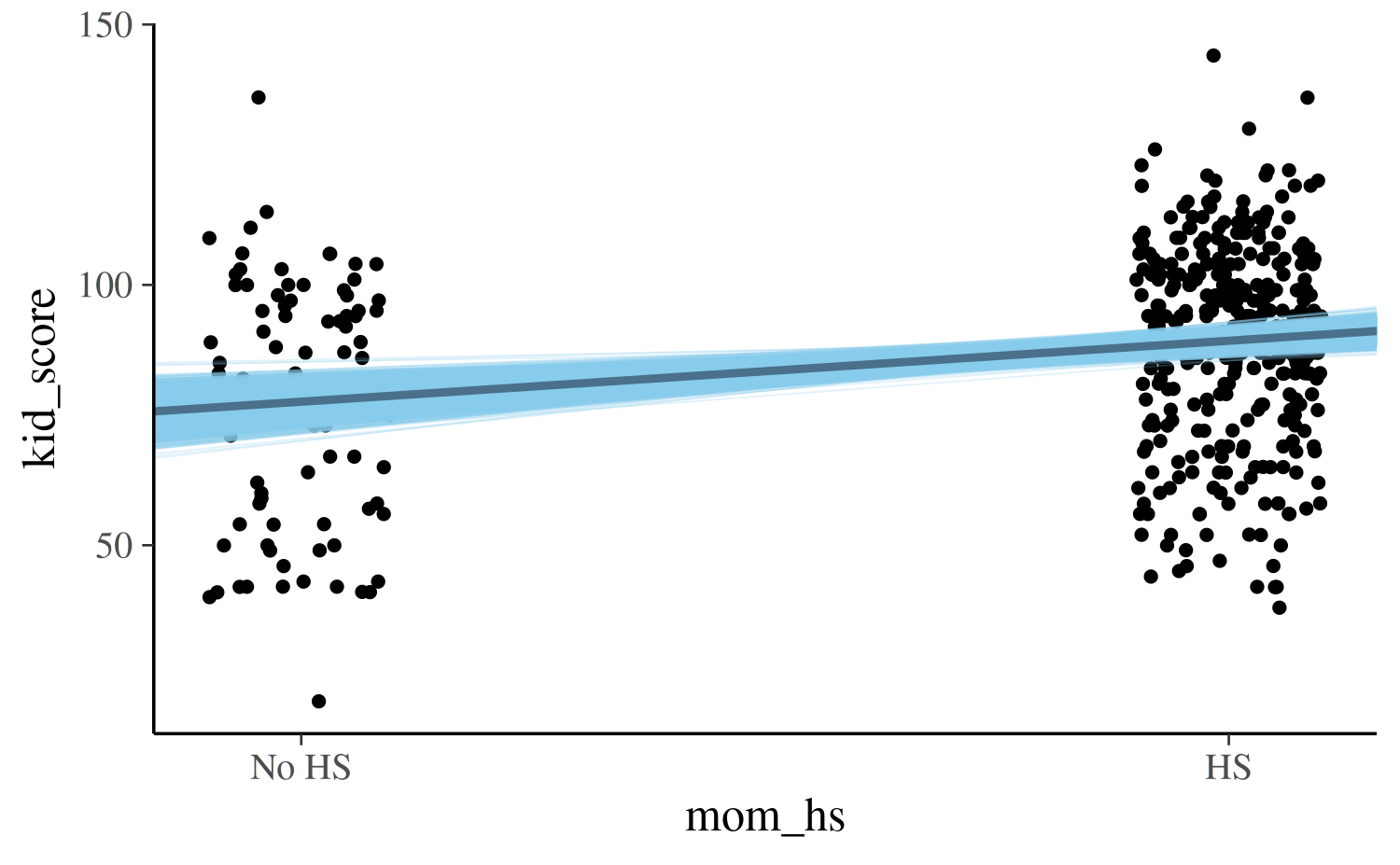

There several ways we could add the uncertainty in our estimates to

the plot. One way is to also plot the estimated regression line at each

draw from the posterior distribution. To do this we can extract the

posterior draws from the fitted model object using the

as.matrix or as.data.frame methods:

draws <- as.data.frame(post1)

colnames(draws)[1:2] <- c("a", "b")

base +

geom_abline(data = draws, aes(intercept = a, slope = b),

color = "skyblue", size = 0.2, alpha = 0.25) +

geom_abline(intercept = coef(post1)[1], slope = coef(post1)[2],

color = "skyblue4", size = 1)

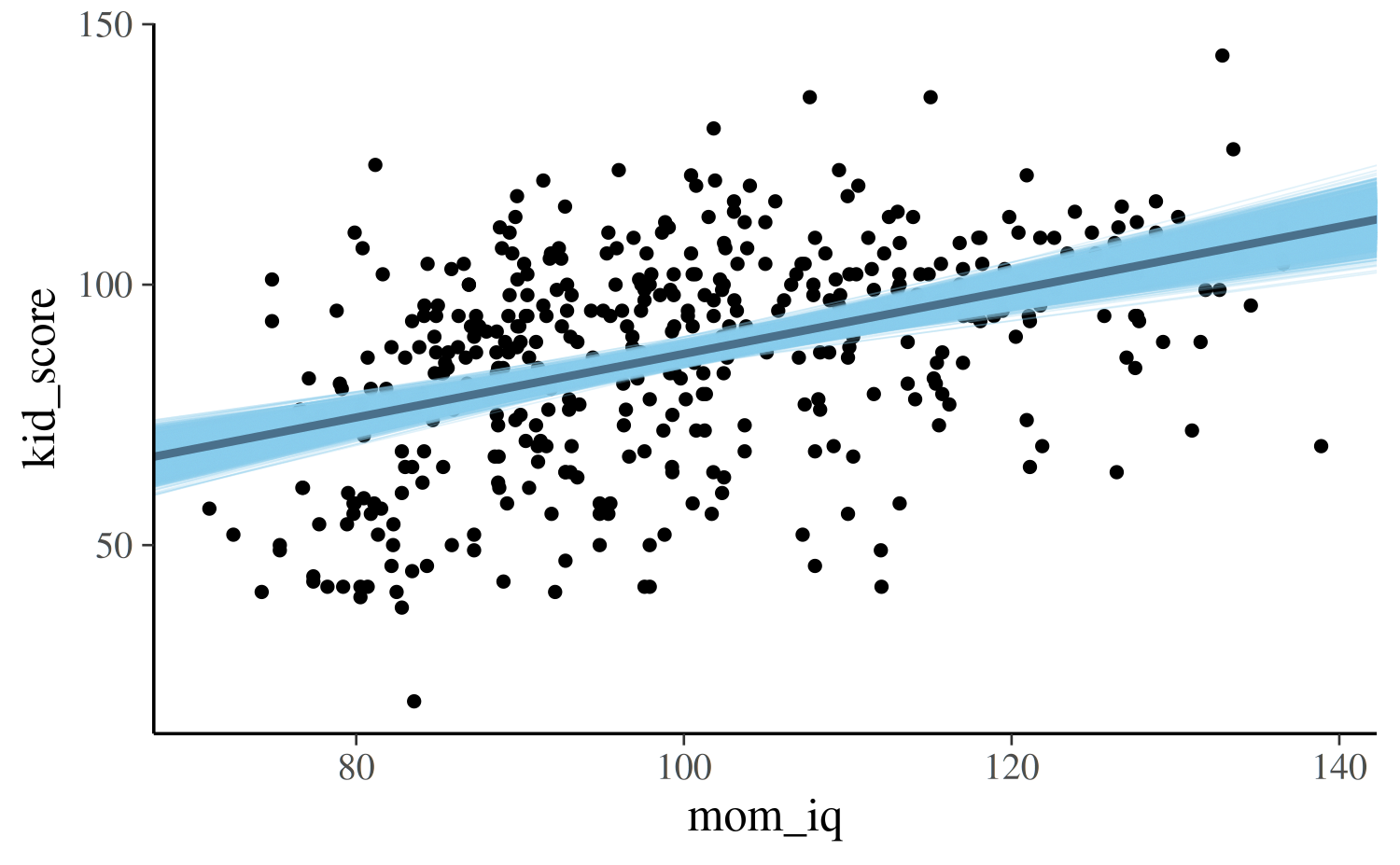

For the second model we can make the same plot but the x-axis will

show the continuous predictor mom_iq:

draws <- as.data.frame(as.matrix(post2))

colnames(draws)[1:2] <- c("a", "b")

ggplot(kidiq, aes(x = mom_iq, y = kid_score)) +

geom_point(size = 1) +

geom_abline(data = draws, aes(intercept = a, slope = b),

color = "skyblue", size = 0.2, alpha = 0.25) +

geom_abline(intercept = coef(post2)[1], slope = coef(post2)[2],

color = "skyblue4", size = 1)

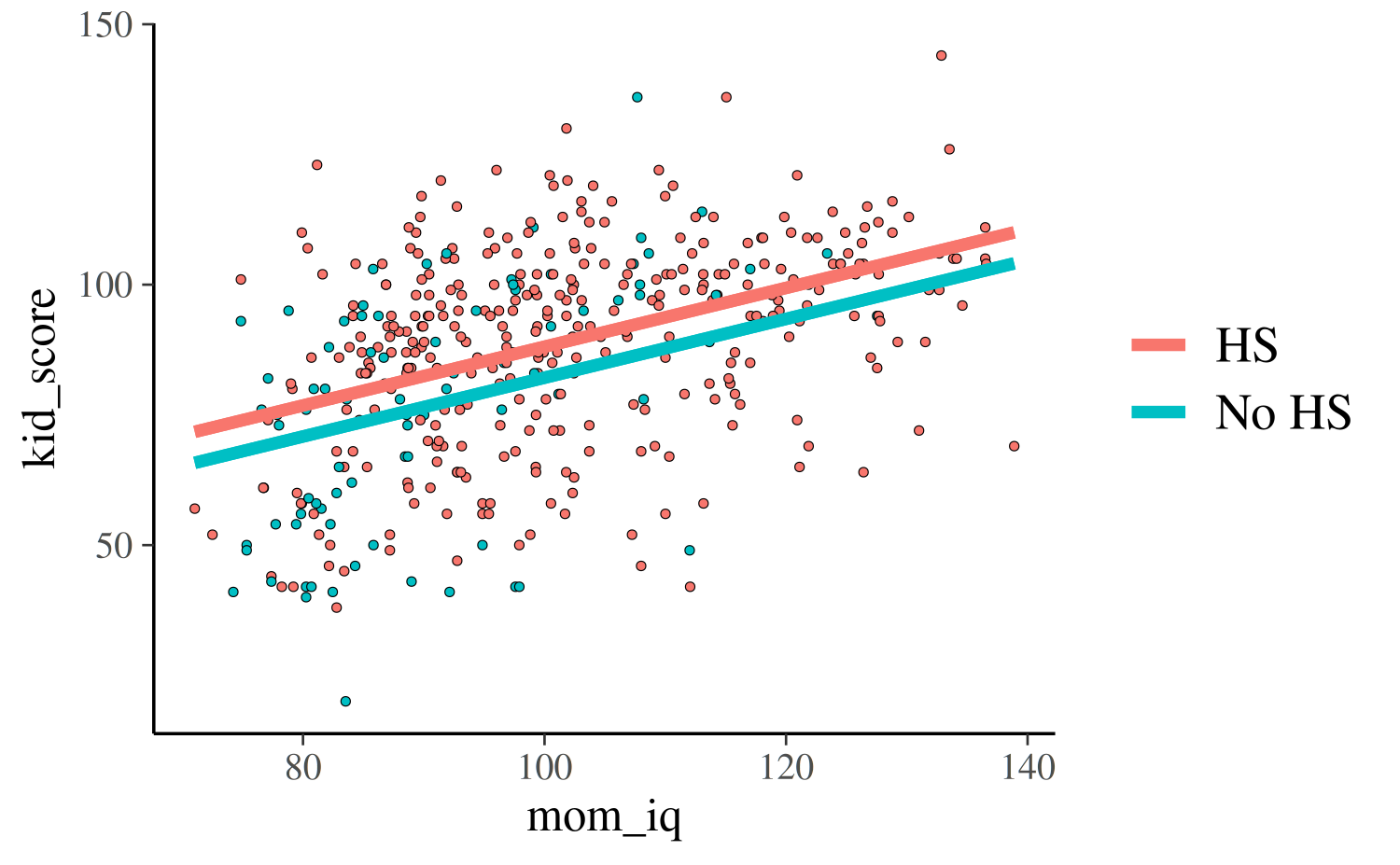

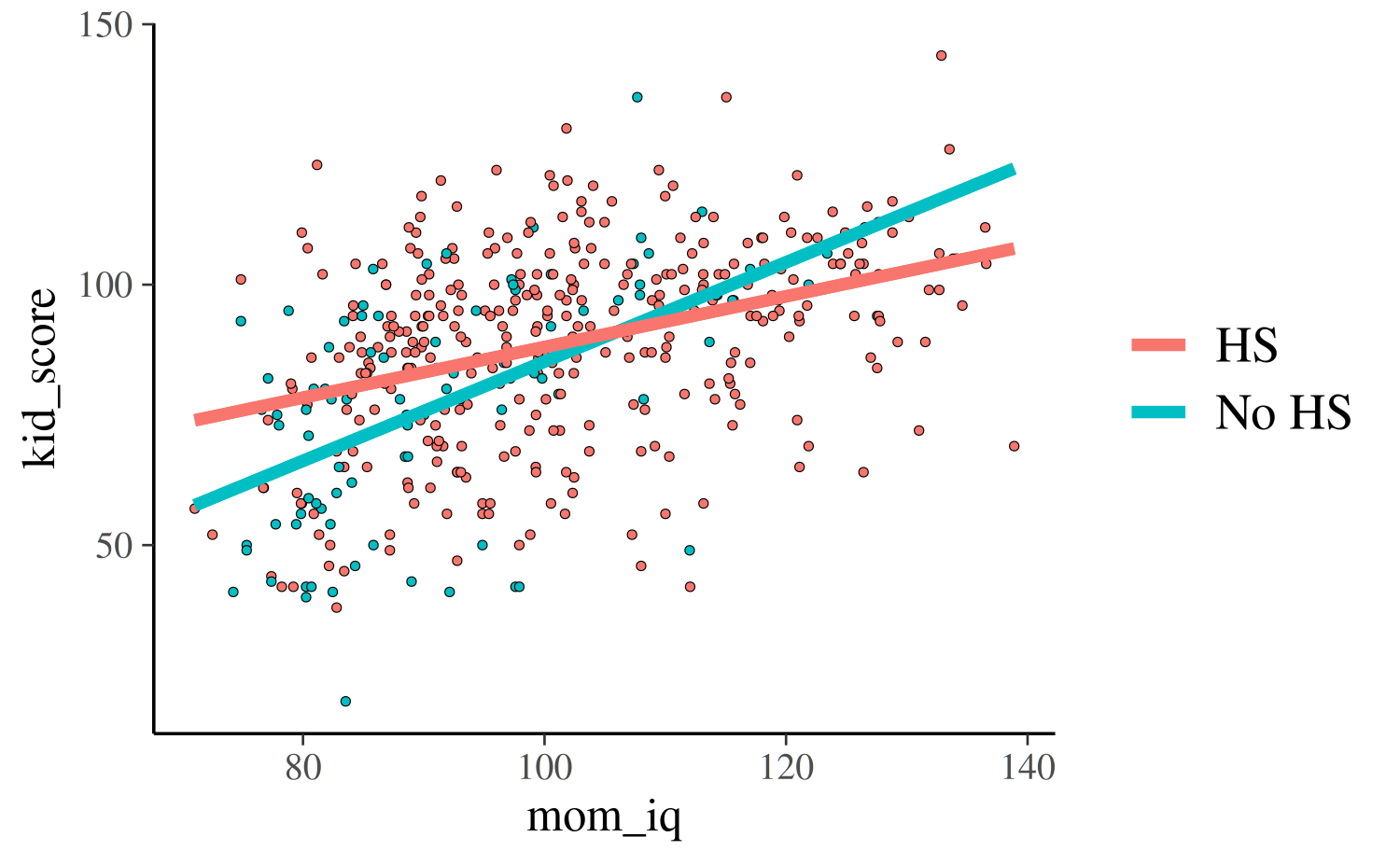

For the third and fourth models, each of which uses both predictors,

we can plot the continuous mom_iq on the x-axis and use

color to indicate which points correspond to the different

subpopulations defined by mom_hs. We also now plot two

regression lines, one for each subpopulation:

reg0 <- function(x, ests) cbind(1, 0, x) %*% ests

reg1 <- function(x, ests) cbind(1, 1, x) %*% ests

args <- list(ests = coef(post3))

kidiq$clr <- factor(kidiq$mom_hs, labels = c("No HS", "HS"))

lgnd <- guide_legend(title = NULL)

base2 <- ggplot(kidiq, aes(x = mom_iq, fill = relevel(clr, ref = "HS"))) +

geom_point(aes(y = kid_score), shape = 21, stroke = .2, size = 1) +

guides(color = lgnd, fill = lgnd) +

theme(legend.position = "right")

base2 +

stat_function(fun = reg0, args = args, aes(color = "No HS"), size = 1.5) +

stat_function(fun = reg1, args = args, aes(color = "HS"), size = 1.5)

reg0 <- function(x, ests) cbind(1, 0, x, 0 * x) %*% ests

reg1 <- function(x, ests) cbind(1, 1, x, 1 * x) %*% ests

args <- list(ests = coef(post4))

base2 +

stat_function(fun = reg0, args = args, aes(color = "No HS"), size = 1.5) +

stat_function(fun = reg1, args = args, aes(color = "HS"), size = 1.5)

Model comparison

One way we can compare the four contending models is to use an

approximation to Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation, which is

implemented by the loo function in the loo

package:

# Compare them with loo

loo1 <- loo(post1, cores = 1)

loo2 <- loo(post2, cores = 1)

loo3 <- loo(post3, cores = 1)

loo4 <- loo(post4, cores = 1)

(comp <- loo_compare(loo1, loo2, loo3, loo4)) elpd_diff se_diff

post4 0.0 0.0

post3 -3.5 2.7

post2 -6.2 4.1

post1 -42.4 8.7 In this case the fourth model is preferred as it has the highest

expected log predicted density (elpd_loo) or, equivalently,

the lowest value of the LOO Information Criterion (looic).

The fourth model is preferred by a lot over the first model

loo_compare(loo1, loo4) elpd_diff se_diff

post4 0.0 0.0

post1 -42.4 8.7 because the difference in elpd is so much larger than

the standard error. However, the preference of the fourth model over the

others isn’t as strong:

loo_compare(loo3, loo4) elpd_diff se_diff

post4 0.0 0.0

post3 -3.5 2.7

loo_compare(loo2, loo4) elpd_diff se_diff

post4 0.0 0.0

post2 -6.2 4.1 The posterior predictive distribution

The posterior predictive distribution is the distribution of the outcome implied by the model after using the observed data to update our beliefs about the unknown parameters. When simulating observations from the posterior predictive distribution we use the notation \(y^{\rm rep}\) (for replicate) when we use the same observations of \(X\) that were used to estimate the model parameters. When \(X\) contains new observations we use the notation \(\tilde{y}\) to refer to the posterior predictive simulations.

Simulating data from the posterior predictive distribution using the observed predictors is useful for checking the fit of the model. Drawing from the posterior predictive distribution at interesting values of the predictors also lets us visualize how a manipulation of a predictor affects (a function of) the outcome(s).

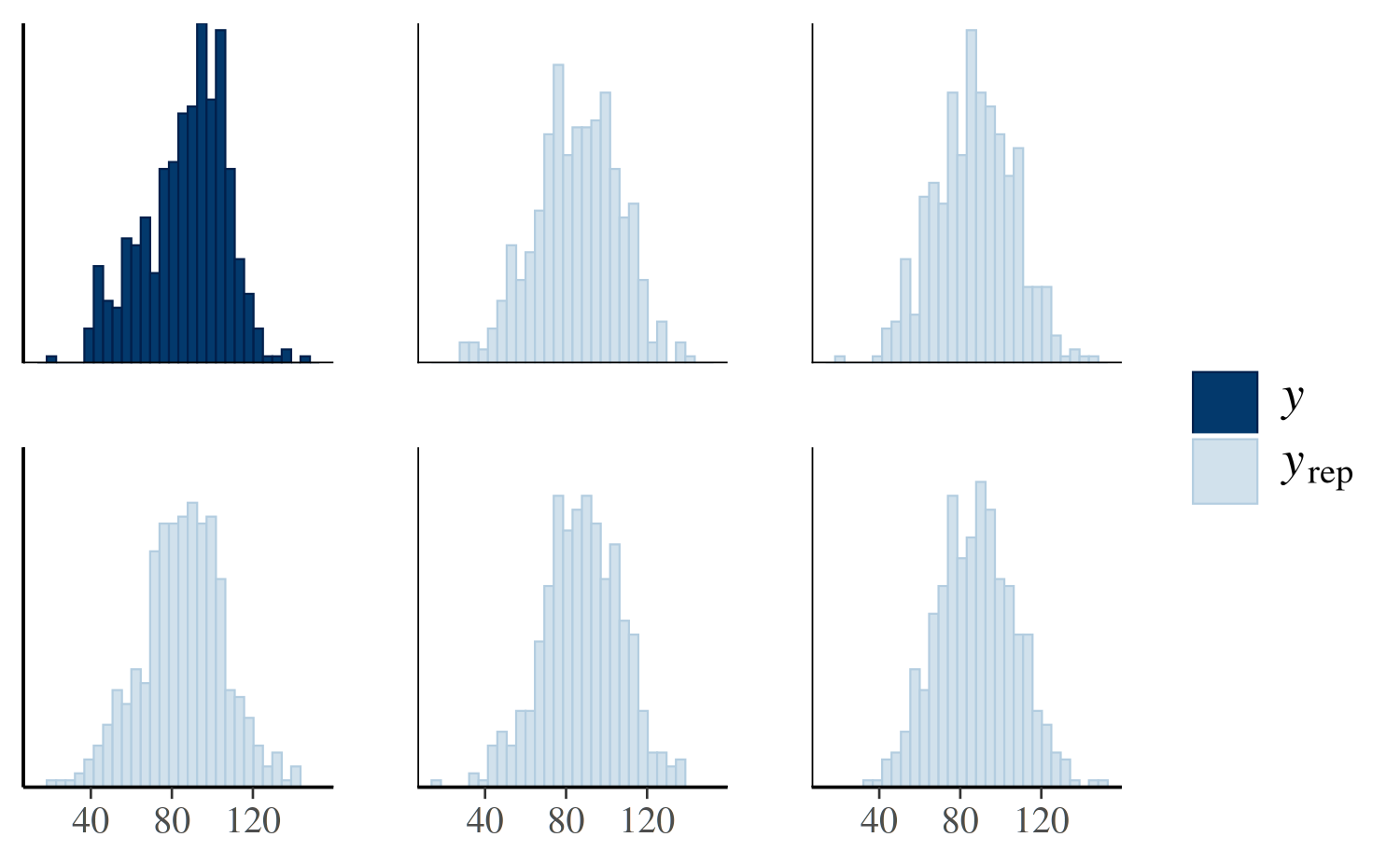

Graphical posterior predictive checks

The pp_check function generates a variety of plots

comparing the observed outcome \(y\) to

simulated datasets \(y^{\rm rep}\) from

the posterior predictive distribution using the same observations of the

predictors \(X\) as we used to fit the

model. He we show a few of the possible displays. The documentation at

help("pp_check.stanreg", package = "rstanarm") has details

on all of the pp_check options.

First we’ll look at a plot directly comparing the distributions of

\(y\) and \(y^{\rm rep}\). The following call to

pp_check will create a plot juxtaposing the histogram of

\(y\) and histograms of five \(y^{\rm rep}\) datasets:

pp_check(post4, plotfun = "hist", nreps = 5)

The idea is that if the model is a good fit to the data we should be able to generate data \(y^{\rm rep}\) from the posterior predictive distribution that looks a lot like the observed data \(y\). That is, given \(y\), the \(y^{\rm rep}\) we generate should be plausible.

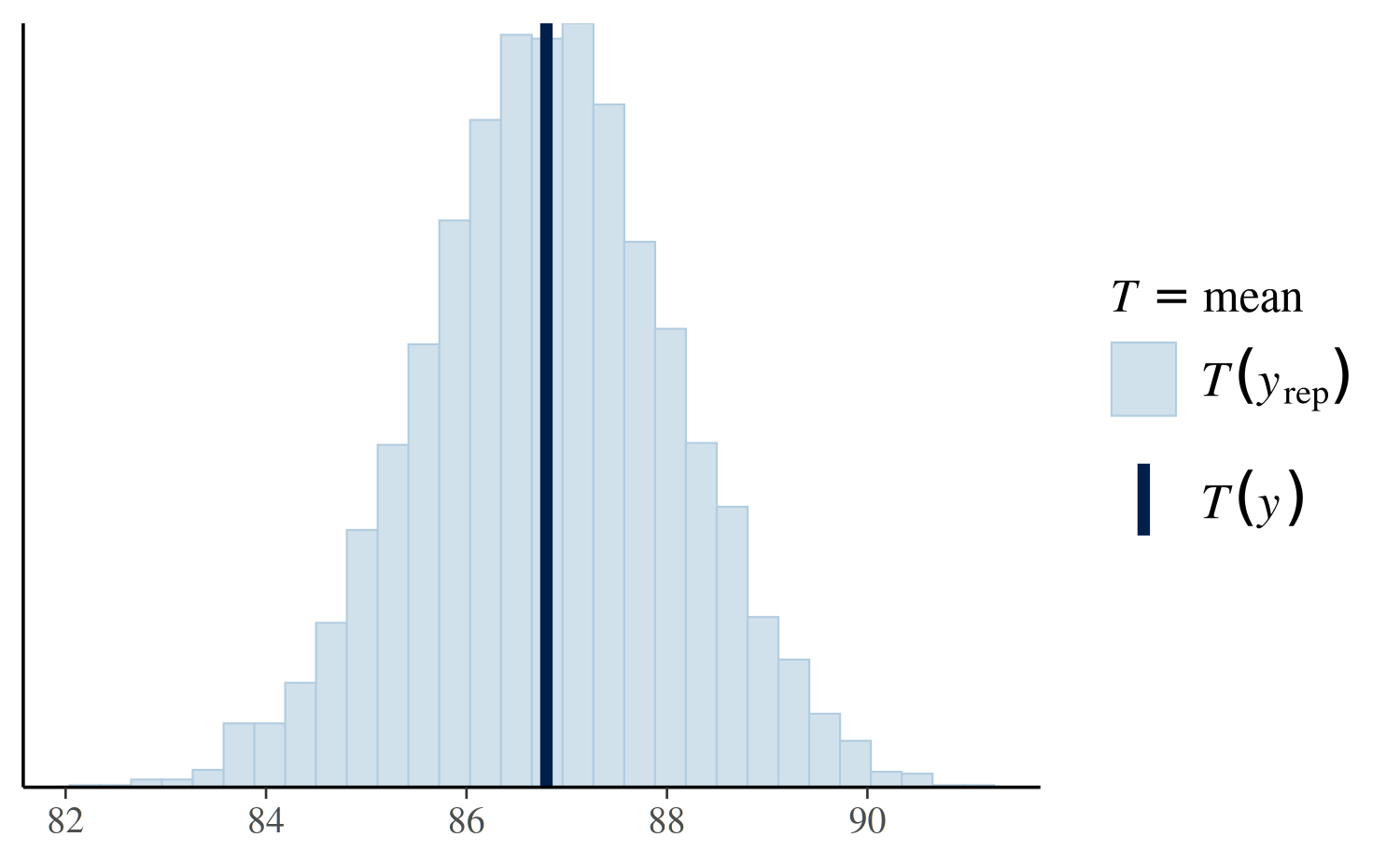

Another useful plot we can make using pp_check shows the

distribution of a test quantity \(T(y^{\rm

rep})\) compared to \(T(y)\),

the value of the quantity in the observed data. When the argument

plotfun = "stat" is specified, pp_check will

simulate \(S\) datasets \(y_1^{\rm rep}, \dots, y_S^{\rm rep}\), each

containing \(N\) observations. Here

\(S\) is the size of the posterior

sample (the number of MCMC draws from the posterior distribution of the

model parameters) and \(N\) is the

length of \(y\). We can then check if

\(T(y)\) is consistent with the

distribution of \(\left(T(y_1^{\rm yep}),

\dots, T(y_S^{\rm yep})\right)\). In the plot below we see that

the mean of the observations is plausible when compared to the

distribution of the means of the \(S\)

\(y^{\rm rep}\) datasets:

pp_check(post4, plotfun = "stat", stat = "mean")

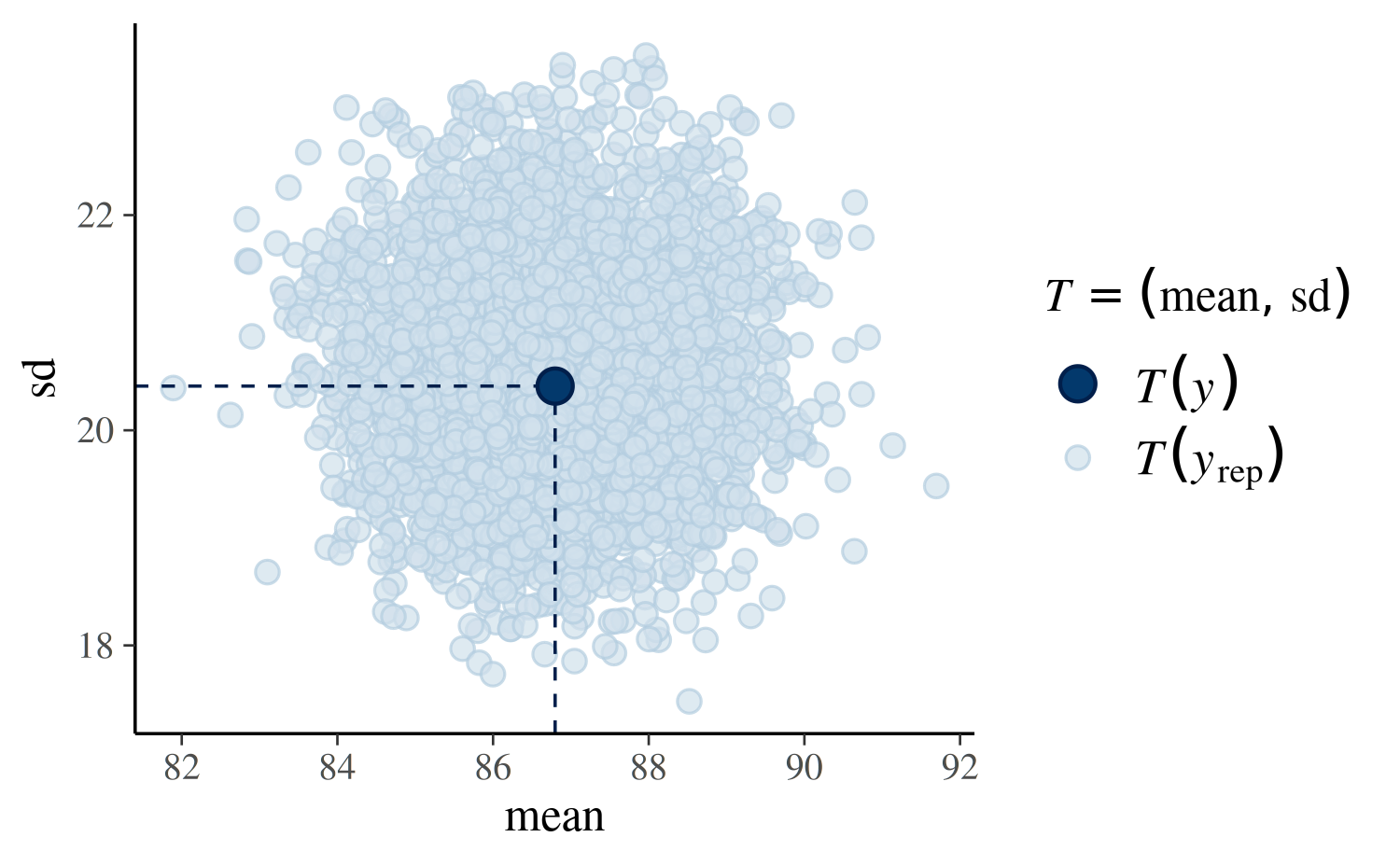

Using plotfun="stat_2d" we can also specify two test

quantities and look at a scatterplot:

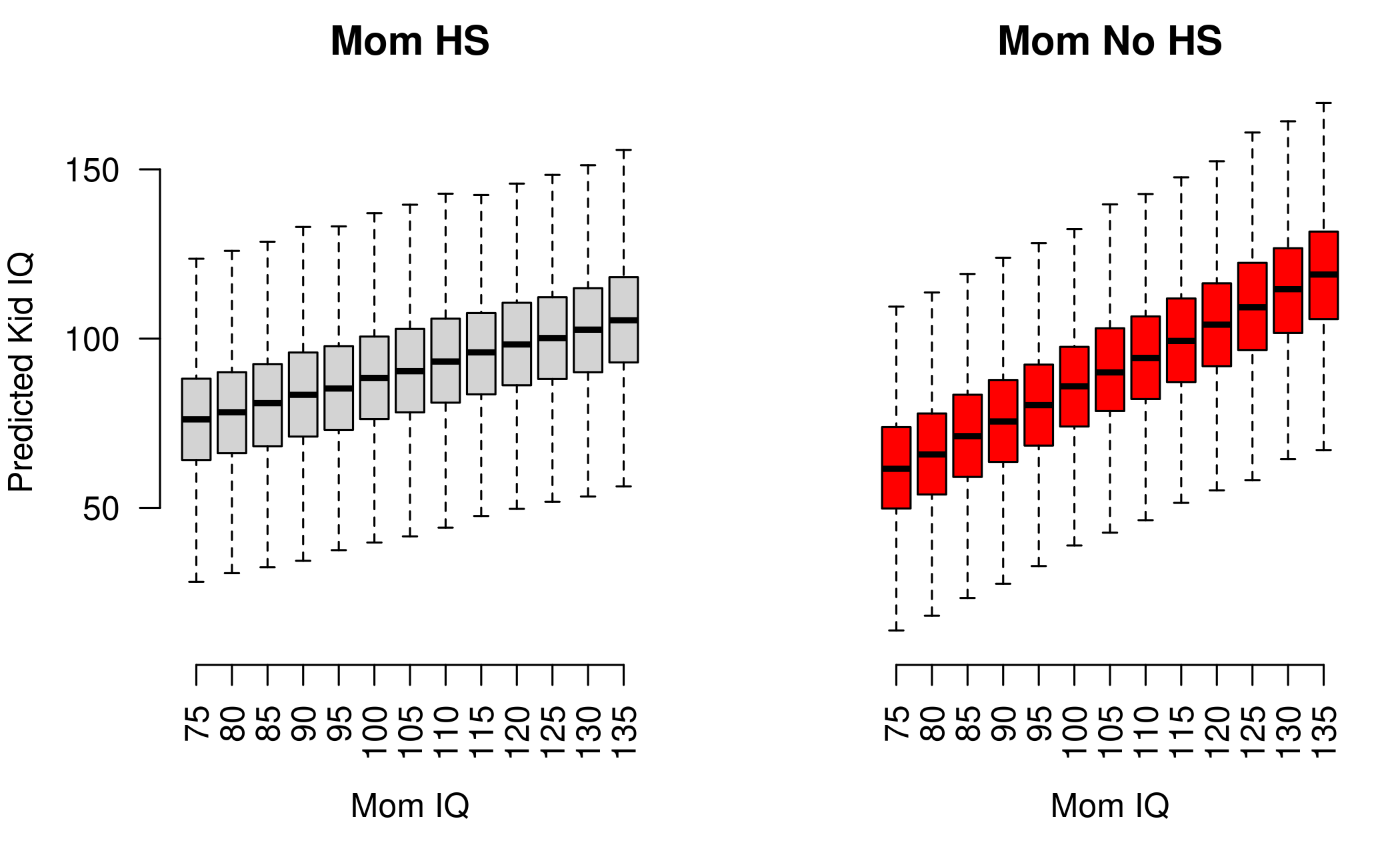

Generating predictions

The posterior_predict function is used to generate

replicated data \(y^{\rm

rep}\) or predictions for future observations \(\tilde{y}\). Here we show how to use

posterior_predict to generate predictions of the outcome

kid_score for a range of different values of

mom_iq and for both subpopulations defined by

mom_hs.

IQ_SEQ <- seq(from = 75, to = 135, by = 5)

y_nohs <- posterior_predict(post4, newdata = data.frame(mom_hs = 0, mom_iq = IQ_SEQ))

y_hs <- posterior_predict(post4, newdata = data.frame(mom_hs = 1, mom_iq = IQ_SEQ))

dim(y_hs)[1] 4000 13We now have two matrices, y_nohs and y_hs.

Each matrix has as many columns as there are values of

IQ_SEQ and as many rows as the size of the posterior

sample. One way to show the predictors is to plot the predictions for

the two groups of kids side by side:

par(mfrow = c(1:2), mar = c(5,4,2,1))

boxplot(y_hs, axes = FALSE, outline = FALSE, ylim = c(10,170),

xlab = "Mom IQ", ylab = "Predicted Kid IQ", main = "Mom HS")

axis(1, at = 1:ncol(y_hs), labels = IQ_SEQ, las = 3)

axis(2, las = 1)

boxplot(y_nohs, outline = FALSE, col = "red", axes = FALSE, ylim = c(10,170),

xlab = "Mom IQ", ylab = NULL, main = "Mom No HS")

axis(1, at = 1:ncol(y_hs), labels = IQ_SEQ, las = 3)

Gamma Regression Example

Gamma regression is often used when the response variable is continuous and positive, and the coefficient of variation (rather than the variance) is constant.

We’ll use one of the standard examples of Gamma regression, which is

taken from McCullagh & Nelder (1989). This example is also given in

the documentation for R’s glm function. The outcome of

interest is the clotting time of blood (in seconds) for “normal plasma

diluted to nine different percentage concentrations with

prothrombin-free plasma; clotting was induced by two lots of

thromboplastin” (p. 300).

The help page for R’s glm function presents the example

as follows:

clotting <- data.frame(

u = c(5,10,15,20,30,40,60,80,100),

lot1 = c(118,58,42,35,27,25,21,19,18),

lot2 = c(69,35,26,21,18,16,13,12,12))

summary(glm(lot1 ~ log(u), data = clotting, family = Gamma))

summary(glm(lot2 ~ log(u), data = clotting, family = Gamma))To fit the analogous Bayesian models we can simply substitute

stan_glm for glm above. However, instead of

fitting separate models we can also reshape the data slightly and fit a

model interacting lot with plasma concentration:

clotting2 <- with(clotting, data.frame(

log_plasma = rep(log(u), 2),

clot_time = c(lot1, lot2),

lot_id = factor(rep(c(1,2), each = length(u)))

))

fit <- stan_glm(clot_time ~ log_plasma * lot_id, data = clotting2, family = Gamma,

prior_intercept = normal(0, 1, autoscale = TRUE),

prior = normal(0, 1, autoscale = TRUE),

seed = 12345)

print(fit, digits = 3)stan_glm

family: Gamma [inverse]

formula: clot_time ~ log_plasma * lot_id

observations: 18

predictors: 4

------

Median MAD_SD

(Intercept) -0.016 0.007

log_plasma 0.015 0.003

lot_id2 -0.007 0.014

log_plasma:lot_id2 0.008 0.006

Auxiliary parameter(s):

Median MAD_SD

shape 7.982 2.756

------

* For help interpreting the printed output see ?print.stanreg

* For info on the priors used see ?prior_summary.stanregIn the output above, the estimate reported for shape is

for the shape parameter of the Gamma distribution. The

reciprocal of the shape parameter can be interpreted similarly

to what summary.glm refers to as the dispersion

parameter.