The functions described on this page are used to specify the

prior-related arguments of the various modeling functions in the

rstanarm package (to view the priors used for an existing model see

prior_summary).

The default priors used in the various rstanarm modeling functions

are intended to be weakly informative in that they provide moderate

regularization and help stabilize computation. For many applications the

defaults will perform well, but prudent use of more informative priors is

encouraged. Uniform prior distributions are possible (e.g. by setting

stan_glm's prior argument to NULL) but, unless

the data is very strong, they are not recommended and are not

non-informative, giving the same probability mass to implausible values as

plausible ones.

More information on priors is available in the vignette Prior Distributions for rstanarm Models as well as the vignettes for the various modeling functions. For details on the priors used for multilevel models in particular see the vignette Estimating Generalized (Non-)Linear Models with Group-Specific Terms with rstanarm and also the Covariance matrices section lower down on this page.

Usage

normal(location = 0, scale = NULL, autoscale = FALSE)

student_t(df = 1, location = 0, scale = NULL, autoscale = FALSE)

cauchy(location = 0, scale = NULL, autoscale = FALSE)

hs(df = 1, global_df = 1, global_scale = 0.01, slab_df = 4, slab_scale = 2.5)

hs_plus(

df1 = 1,

df2 = 1,

global_df = 1,

global_scale = 0.01,

slab_df = 4,

slab_scale = 2.5

)

laplace(location = 0, scale = NULL, autoscale = FALSE)

lasso(df = 1, location = 0, scale = NULL, autoscale = FALSE)

product_normal(df = 2, location = 0, scale = 1)

exponential(rate = 1, autoscale = FALSE)

decov(regularization = 1, concentration = 1, shape = 1, scale = 1)

lkj(regularization = 1, scale = 10, df = 1, autoscale = TRUE)

dirichlet(concentration = 1)

R2(location = NULL, what = c("mode", "mean", "median", "log"))

default_prior_intercept(family)

default_prior_coef(family)Arguments

- location

Prior location. In most cases, this is the prior mean, but for

cauchy(which is equivalent tostudent_twithdf=1), the mean does not exist andlocationis the prior median. The default value is \(0\), except forR2which has no default value forlocation. ForR2,locationpertains to the prior location of the \(R^2\) under a Beta distribution, but the interpretation of thelocationparameter depends on the specified value of thewhatargument (see the R2 family section in Details).- scale

Prior scale. The default depends on the family (see Details).

- autoscale

If

TRUEthen the scales of the priors on the intercept and regression coefficients may be additionally modified internally by rstanarm in the following cases. First, for Gaussian models only, the prior scales for the intercept, coefficients, and the auxiliary parametersigma(error standard deviation) are multiplied bysd(y). Additionally — not only for Gaussian models — if theQRargument to the model fitting function (e.g.stan_glm) isFALSEthen we also divide the prior scale(s) bysd(x). Prior autoscaling is also discussed in the vignette Prior Distributions for rstanarm Models- df, df1, df2

Prior degrees of freedom. The default is \(1\) for

student_t, in which case it is equivalent tocauchy. For the hierarchical shrinkage priors (hsandhs_plus) the degrees of freedom parameter(s) default to \(1\). For theproduct_normalprior, the degrees of freedom parameter must be an integer (vector) that is at least \(2\) (the default).- global_df, global_scale, slab_df, slab_scale

Optional arguments for the hierarchical shrinkage priors. See the Hierarchical shrinkage family section below.

- rate

Prior rate for the exponential distribution. Defaults to

1. For the exponential distribution, the rate parameter is the reciprocal of the mean.- regularization

Exponent for an LKJ prior on the correlation matrix in the

decovorlkjprior. The default is \(1\), implying a joint uniform prior.- concentration

Concentration parameter for a symmetric Dirichlet distribution. The default is \(1\), implying a joint uniform prior.

- shape

Shape parameter for a gamma prior on the scale parameter in the

decovprior. Ifshapeandscaleare both \(1\) (the default) then the gamma prior simplifies to the unit-exponential distribution.- what

A character string among

'mode'(the default),'mean','median', or'log'indicating how thelocationparameter is interpreted in theLKJcase. If'log', thenlocationis interpreted as the expected logarithm of the \(R^2\) under a Beta distribution. Otherwise,locationis interpreted as thewhatof the \(R^2\) under a Beta distribution. If the number of predictors is less than or equal to two, the mode of this Beta distribution does not exist and an error will prompt the user to specify another choice forwhat.- family

Not currently used.

Details

The details depend on the family of the prior being used:

Student t family

Family members:

normal(location, scale)student_t(df, location, scale)cauchy(location, scale)

Each of these functions also takes an argument autoscale.

For the prior distribution for the intercept, location,

scale, and df should be scalars. For the prior for the other

coefficients they can either be vectors of length equal to the number of

coefficients (not including the intercept), or they can be scalars, in

which case they will be recycled to the appropriate length. As the

degrees of freedom approaches infinity, the Student t distribution

approaches the normal distribution and if the degrees of freedom are one,

then the Student t distribution is the Cauchy distribution.

If scale is not specified it will default to \(2.5\), unless the

probit link function is used, in which case these defaults are scaled by a

factor of dnorm(0)/dlogis(0), which is roughly \(1.6\).

If the autoscale argument is TRUE, then the

scales will be further adjusted as described above in the documentation of

the autoscale argument in the Arguments section.

Hierarchical shrinkage family

Family members:

hs(df, global_df, global_scale, slab_df, slab_scale)hs_plus(df1, df2, global_df, global_scale, slab_df, slab_scale)

The hierarchical shrinkage priors are normal with a mean of zero and a

standard deviation that is also a random variable. The traditional

hierarchical shrinkage prior utilizes a standard deviation that is

distributed half Cauchy with a median of zero and a scale parameter that is

also half Cauchy. This is called the "horseshoe prior". The hierarchical

shrinkage (hs) prior in the rstanarm package instead utilizes

a regularized horseshoe prior, as described by Piironen and Vehtari (2017),

which recommends setting the global_scale argument equal to the ratio

of the expected number of non-zero coefficients to the expected number of

zero coefficients, divided by the square root of the number of observations.

The hierarhical shrinkpage plus (hs_plus) prior is similar except

that the standard deviation that is distributed as the product of two

independent half Cauchy parameters that are each scaled in a similar way

to the hs prior.

The hierarchical shrinkage priors have very tall modes and very fat tails.

Consequently, they tend to produce posterior distributions that are very

concentrated near zero, unless the predictor has a strong influence on the

outcome, in which case the prior has little influence. Hierarchical

shrinkage priors often require you to increase the

adapt_delta tuning parameter in order to diminish the number

of divergent transitions. For more details on tuning parameters and

divergent transitions see the Troubleshooting section of the How to

Use the rstanarm Package vignette.

Laplace family

Family members:

laplace(location, scale)lasso(df, location, scale)

Each of these functions also takes an argument autoscale.

The Laplace distribution is also known as the double-exponential distribution. It is a symmetric distribution with a sharp peak at its mean / median / mode and fairly long tails. This distribution can be motivated as a scale mixture of normal distributions and the remarks above about the normal distribution apply here as well.

The lasso approach to supervised learning can be expressed as finding the

posterior mode when the likelihood is Gaussian and the priors on the

coefficients have independent Laplace distributions. It is commonplace in

supervised learning to choose the tuning parameter by cross-validation,

whereas a more Bayesian approach would be to place a prior on “it”,

or rather its reciprocal in our case (i.e. smaller values correspond

to more shrinkage toward the prior location vector). We use a chi-square

prior with degrees of freedom equal to that specified in the call to

lasso or, by default, 1. The expectation of a chi-square random

variable is equal to this degrees of freedom and the mode is equal to the

degrees of freedom minus 2, if this difference is positive.

It is also common in supervised learning to standardize the predictors

before training the model. We do not recommend doing so. Instead, it is

better to specify autoscale = TRUE, which

will adjust the scales of the priors according to the dispersion in the

variables. See the documentation of the autoscale argument above

and also the prior_summary page for more information.

Product-normal family

Family members:

product_normal(df, location, scale)

The product-normal distribution is the product of at least two independent

normal variates each with mean zero, shifted by the location

parameter. It can be shown that the density of a product-normal variate is

symmetric and infinite at location, so this prior resembles a

“spike-and-slab” prior for sufficiently large values of the

scale parameter. For better or for worse, this prior may be

appropriate when it is strongly believed (by someone) that a regression

coefficient “is” equal to the location, parameter even though

no true Bayesian would specify such a prior.

Each element of df must be an integer of at least \(2\) because

these “degrees of freedom” are interpreted as the number of normal

variates being multiplied and then shifted by location to yield the

regression coefficient. Higher degrees of freedom produce a sharper

spike at location.

Each element of scale must be a non-negative real number that is

interpreted as the standard deviation of the normal variates being

multiplied and then shifted by location to yield the regression

coefficient. In other words, the elements of scale may differ, but

the k-th standard deviation is presumed to hold for all the normal deviates

that are multiplied together and shifted by the k-th element of

location to yield the k-th regression coefficient. The elements of

scale are not the prior standard deviations of the regression

coefficients. The prior variance of the regression coefficients is equal to

the scale raised to the power of \(2\) times the corresponding element of

df. Thus, larger values of scale put more prior volume on

values of the regression coefficient that are far from zero.

Dirichlet family

Family members:

dirichlet(concentration)

The Dirichlet distribution is a multivariate generalization of the beta distribution. It is perhaps the easiest prior distribution to specify because the concentration parameters can be interpreted as prior counts (although they need not be integers) of a multinomial random variable.

The Dirichlet distribution is used in stan_polr for an

implicit prior on the cutpoints in an ordinal regression model. More

specifically, the Dirichlet prior pertains to the prior probability of

observing each category of the ordinal outcome when the predictors are at

their sample means. Given these prior probabilities, it is straightforward

to add them to form cumulative probabilities and then use an inverse CDF

transformation of the cumulative probabilities to define the cutpoints.

If a scalar is passed to the concentration argument of the

dirichlet function, then it is replicated to the appropriate length

and the Dirichlet distribution is symmetric. If concentration is a

vector and all elements are \(1\), then the Dirichlet distribution is

jointly uniform. If all concentration parameters are equal but greater than

\(1\) then the prior mode is that the categories are equiprobable, and

the larger the value of the identical concentration parameters, the more

sharply peaked the distribution is at the mode. The elements in

concentration can also be given different values to represent that

not all outcome categories are a priori equiprobable.

Covariance matrices

Family members:

decov(regularization, concentration, shape, scale)lkj(regularization, scale, df)

(Also see vignette for stan_glmer,

Estimating

Generalized (Non-)Linear Models with Group-Specific Terms with rstanarm)

Covariance matrices are decomposed into correlation matrices and

variances. The variances are in turn decomposed into the product of a

simplex vector and the trace of the matrix. Finally, the trace is the

product of the order of the matrix and the square of a scale parameter.

This prior on a covariance matrix is represented by the decov

function.

The prior for a correlation matrix is called LKJ whose density is

proportional to the determinant of the correlation matrix raised to the

power of a positive regularization parameter minus one. If

regularization = 1 (the default), then this prior is jointly

uniform over all correlation matrices of that size. If

regularization > 1, then the identity matrix is the mode and in the

unlikely case that regularization < 1, the identity matrix is the

trough.

The trace of a covariance matrix is equal to the sum of the variances. We set the trace equal to the product of the order of the covariance matrix and the square of a positive scale parameter. The particular variances are set equal to the product of a simplex vector — which is non-negative and sums to \(1\) — and the scalar trace. In other words, each element of the simplex vector represents the proportion of the trace attributable to the corresponding variable.

A symmetric Dirichlet prior is used for the simplex vector, which has a

single (positive) concentration parameter, which defaults to

\(1\) and implies that the prior is jointly uniform over the space of

simplex vectors of that size. If concentration > 1, then the prior

mode corresponds to all variables having the same (proportion of total)

variance, which can be used to ensure the the posterior variances are not

zero. As the concentration parameter approaches infinity, this

mode becomes more pronounced. In the unlikely case that

concentration < 1, the variances are more polarized.

If all the variables were multiplied by a number, the trace of their

covariance matrix would increase by that number squared. Thus, it is

reasonable to use a scale-invariant prior distribution for the positive

scale parameter, and in this case we utilize a Gamma distribution, whose

shape and scale are both \(1\) by default, implying a

unit-exponential distribution. Set the shape hyperparameter to some

value greater than \(1\) to ensure that the posterior trace is not zero.

If regularization, concentration, shape and / or

scale are positive scalars, then they are recycled to the

appropriate length. Otherwise, each can be a positive vector of the

appropriate length, but the appropriate length depends on the number of

covariance matrices in the model and their sizes. A one-by-one covariance

matrix is just a variance and thus does not have regularization or

concentration parameters, but does have shape and

scale parameters for the prior standard deviation of that

variable.

Note that for stan_mvmer and stan_jm models an

additional prior distribution is provided through the lkj function.

This prior is in fact currently used as the default for those modelling

functions (although decov is still available as an option if the user

wishes to specify it through the prior_covariance argument). The

lkj prior uses the same decomposition of the covariance matrices

into correlation matrices and variances, however, the variances are not

further decomposed into a simplex vector and the trace; instead the

standard deviations (square root of the variances) for each of the group

specific parameters are given a half Student t distribution with the

scale and df parameters specified through the scale and df

arguments to the lkj function. The scale parameter default is 10

which is then autoscaled, whilst the df parameter default is 1

(therefore equivalent to a half Cauchy prior distribution for the

standard deviation of each group specific parameter). This prior generally

leads to similar results as the decov prior, but it is also likely

to be **less** diffuse compared with the decov prior; therefore it

sometimes seems to lead to faster estimation times, hence why it has

been chosen as the default prior for stan_mvmer and

stan_jm where estimation times can be long.

R2 family

Family members:

R2(location, what)

The stan_lm, stan_aov, and

stan_polr functions allow the user to utilize a function

called R2 to convey prior information about all the parameters.

This prior hinges on prior beliefs about the location of \(R^2\), the

proportion of variance in the outcome attributable to the predictors,

which has a Beta prior with first shape

hyperparameter equal to half the number of predictors and second shape

hyperparameter free. By specifying what to be the prior mode (the

default), mean, median, or expected log of \(R^2\), the second shape

parameter for this Beta distribution is determined internally. If

what = 'log', location should be a negative scalar; otherwise it

should be a scalar on the \((0,1)\) interval.

For example, if \(R^2 = 0.5\), then the mode, mean, and median of

the Beta distribution are all the same and thus the

second shape parameter is also equal to half the number of predictors.

The second shape parameter of the Beta distribution

is actually the same as the shape parameter in the LKJ prior for a

correlation matrix described in the previous subsection. Thus, the smaller

is \(R^2\), the larger is the shape parameter, the smaller are the

prior correlations among the outcome and predictor variables, and the more

concentrated near zero is the prior density for the regression

coefficients. Hence, the prior on the coefficients is regularizing and

should yield a posterior distribution with good out-of-sample predictions

if the prior location of \(R^2\) is specified in a reasonable

fashion.

References

Gelman, A., Carlin, J. B., Stern, H. S., Dunson, D. B., Vehtari, A., and Rubin, D. B. (2013). Bayesian Data Analysis. Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, London, third edition. https://stat.columbia.edu/~gelman/book/

Gelman, A., Jakulin, A., Pittau, M. G., and Su, Y. (2008). A weakly informative default prior distribution for logistic and other regression models. Annals of Applied Statistics. 2(4), 1360–1383.

Piironen, J., and Vehtari, A. (2017). Sparsity information and regularization in the horseshoe and other shrinkage priors. https://arxiv.org/abs/1707.01694

Stan Development Team. Stan Modeling Language Users Guide and Reference Manual. https://mc-stan.org/users/documentation/.

See also

The various vignettes for the rstanarm package also discuss and demonstrate the use of some of the supported prior distributions.

Examples

if (.Platform$OS.type != "windows" || .Platform$r_arch != "i386") {

fmla <- mpg ~ wt + qsec + drat + am

# Draw from prior predictive distribution (by setting prior_PD = TRUE)

prior_pred_fit <- stan_glm(fmla, data = mtcars, prior_PD = TRUE,

chains = 1, seed = 12345, iter = 250, # for speed only

prior = student_t(df = 4, 0, 2.5),

prior_intercept = cauchy(0,10),

prior_aux = exponential(1/2))

plot(prior_pred_fit, "hist")

# \donttest{

# Can assign priors to names

N05 <- normal(0, 5)

fit <- stan_glm(fmla, data = mtcars, prior = N05, prior_intercept = N05)

# }

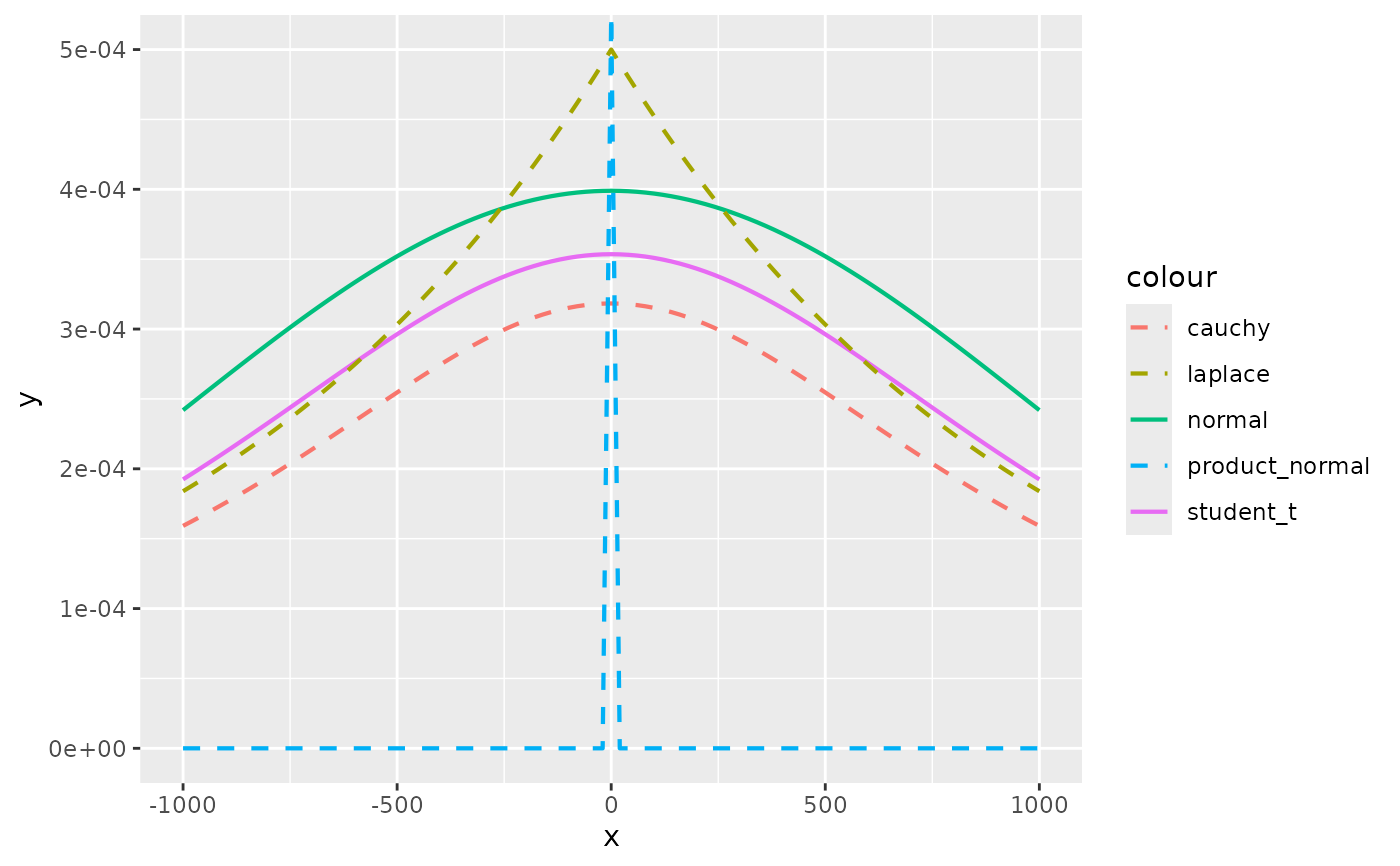

# Visually compare normal, student_t, cauchy, laplace, and product_normal

compare_priors <- function(scale = 1, df_t = 2, xlim = c(-10, 10)) {

dt_loc_scale <- function(x, df, location, scale) {

1/scale * dt((x - location)/scale, df)

}

dlaplace <- function(x, location, scale) {

0.5 / scale * exp(-abs(x - location) / scale)

}

dproduct_normal <- function(x, scale) {

besselK(abs(x) / scale ^ 2, nu = 0) / (scale ^ 2 * pi)

}

stat_dist <- function(dist, ...) {

ggplot2::stat_function(ggplot2::aes_(color = dist), ...)

}

ggplot2::ggplot(data.frame(x = xlim), ggplot2::aes(x)) +

stat_dist("normal", size = .75, fun = dnorm,

args = list(mean = 0, sd = scale)) +

stat_dist("student_t", size = .75, fun = dt_loc_scale,

args = list(df = df_t, location = 0, scale = scale)) +

stat_dist("cauchy", size = .75, linetype = 2, fun = dcauchy,

args = list(location = 0, scale = scale)) +

stat_dist("laplace", size = .75, linetype = 2, fun = dlaplace,

args = list(location = 0, scale = scale)) +

stat_dist("product_normal", size = .75, linetype = 2, fun = dproduct_normal,

args = list(scale = 1))

}

# Cauchy has fattest tails, followed by student_t, laplace, and normal

compare_priors()

# The student_t with df = 1 is the same as the cauchy

compare_priors(df_t = 1)

# Even a scale of 5 is somewhat large. It gives plausibility to rather

# extreme values

compare_priors(scale = 5, xlim = c(-20,20))

# If you use a prior like normal(0, 1000) to be "non-informative" you are

# actually saying that a coefficient value of e.g. -500 is quite plausible

compare_priors(scale = 1000, xlim = c(-1000,1000))

}

#>

#> SAMPLING FOR MODEL 'continuous' NOW (CHAIN 1).

#> Chain 1:

#> Chain 1: Gradient evaluation took 2.1e-05 seconds

#> Chain 1: 1000 transitions using 10 leapfrog steps per transition would take 0.21 seconds.

#> Chain 1: Adjust your expectations accordingly!

#> Chain 1:

#> Chain 1:

#> Chain 1: WARNING: There aren't enough warmup iterations to fit the

#> Chain 1: three stages of adaptation as currently configured.

#> Chain 1: Reducing each adaptation stage to 15%/75%/10% of

#> Chain 1: the given number of warmup iterations:

#> Chain 1: init_buffer = 18

#> Chain 1: adapt_window = 95

#> Chain 1: term_buffer = 12

#> Chain 1:

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 1 / 250 [ 0%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 25 / 250 [ 10%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 50 / 250 [ 20%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 75 / 250 [ 30%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 100 / 250 [ 40%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 125 / 250 [ 50%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 126 / 250 [ 50%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 150 / 250 [ 60%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 175 / 250 [ 70%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 200 / 250 [ 80%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 225 / 250 [ 90%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 250 / 250 [100%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 1:

#> Chain 1: Elapsed Time: 0.022 seconds (Warm-up)

#> Chain 1: 0.023 seconds (Sampling)

#> Chain 1: 0.045 seconds (Total)

#> Chain 1:

#> Warning: The largest R-hat is 1.14, indicating chains have not mixed.

#> Running the chains for more iterations may help. See

#> https://mc-stan.org/misc/warnings.html#r-hat

#> Warning: Bulk Effective Samples Size (ESS) is too low, indicating posterior means and medians may be unreliable.

#> Running the chains for more iterations may help. See

#> https://mc-stan.org/misc/warnings.html#bulk-ess

#> Warning: Tail Effective Samples Size (ESS) is too low, indicating posterior variances and tail quantiles may be unreliable.

#> Running the chains for more iterations may help. See

#> https://mc-stan.org/misc/warnings.html#tail-ess

#>

#> SAMPLING FOR MODEL 'continuous' NOW (CHAIN 1).

#> Chain 1:

#> Chain 1: Gradient evaluation took 1.9e-05 seconds

#> Chain 1: 1000 transitions using 10 leapfrog steps per transition would take 0.19 seconds.

#> Chain 1: Adjust your expectations accordingly!

#> Chain 1:

#> Chain 1:

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 1: Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 1:

#> Chain 1: Elapsed Time: 0.053 seconds (Warm-up)

#> Chain 1: 0.05 seconds (Sampling)

#> Chain 1: 0.103 seconds (Total)

#> Chain 1:

#>

#> SAMPLING FOR MODEL 'continuous' NOW (CHAIN 2).

#> Chain 2:

#> Chain 2: Gradient evaluation took 1.1e-05 seconds

#> Chain 2: 1000 transitions using 10 leapfrog steps per transition would take 0.11 seconds.

#> Chain 2: Adjust your expectations accordingly!

#> Chain 2:

#> Chain 2:

#> Chain 2: Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 2: Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 2: Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 2: Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 2: Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 2: Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 2: Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 2: Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 2: Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 2: Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 2: Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 2: Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 2:

#> Chain 2: Elapsed Time: 0.054 seconds (Warm-up)

#> Chain 2: 0.054 seconds (Sampling)

#> Chain 2: 0.108 seconds (Total)

#> Chain 2:

#>

#> SAMPLING FOR MODEL 'continuous' NOW (CHAIN 3).

#> Chain 3:

#> Chain 3: Gradient evaluation took 1.2e-05 seconds

#> Chain 3: 1000 transitions using 10 leapfrog steps per transition would take 0.12 seconds.

#> Chain 3: Adjust your expectations accordingly!

#> Chain 3:

#> Chain 3:

#> Chain 3: Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 3: Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 3: Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 3: Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 3: Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 3: Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 3: Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 3: Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 3: Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 3: Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 3: Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 3: Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 3:

#> Chain 3: Elapsed Time: 0.054 seconds (Warm-up)

#> Chain 3: 0.067 seconds (Sampling)

#> Chain 3: 0.121 seconds (Total)

#> Chain 3:

#>

#> SAMPLING FOR MODEL 'continuous' NOW (CHAIN 4).

#> Chain 4:

#> Chain 4: Gradient evaluation took 1.1e-05 seconds

#> Chain 4: 1000 transitions using 10 leapfrog steps per transition would take 0.11 seconds.

#> Chain 4: Adjust your expectations accordingly!

#> Chain 4:

#> Chain 4:

#> Chain 4: Iteration: 1 / 2000 [ 0%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 4: Iteration: 200 / 2000 [ 10%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 4: Iteration: 400 / 2000 [ 20%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 4: Iteration: 600 / 2000 [ 30%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 4: Iteration: 800 / 2000 [ 40%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 4: Iteration: 1000 / 2000 [ 50%] (Warmup)

#> Chain 4: Iteration: 1001 / 2000 [ 50%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 4: Iteration: 1200 / 2000 [ 60%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 4: Iteration: 1400 / 2000 [ 70%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 4: Iteration: 1600 / 2000 [ 80%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 4: Iteration: 1800 / 2000 [ 90%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 4: Iteration: 2000 / 2000 [100%] (Sampling)

#> Chain 4:

#> Chain 4: Elapsed Time: 0.056 seconds (Warm-up)

#> Chain 4: 0.055 seconds (Sampling)

#> Chain 4: 0.111 seconds (Total)

#> Chain 4:

#> Warning: `aes_()` was deprecated in ggplot2 3.0.0.

#> ℹ Please use tidy evaluation idioms with `aes()`